Dorothy Counts, center, tried to desegregate Harding High School in Charlotte on Sept. 4, 1957, but met hostility from white classmates and parents. Photo Credit: UNC library collection.

By Keith Poston

An edited version of this article appeared this week in the Charlotte Observer and on the Capitol Broadcasting Opinion page.

On October 8, 1984, President Ronald Reagan made a campaign stop in Charlotte, just weeks shy of his landslide re-election victory.

During the standard campaign stump speech, President Reagan brought up busing for school desegregation, calling such programs failures that “takes innocent children out of the neighborhood school and makes them pawns in a social experiment that nobody wants.”

The previously raucous crowd of Charlotteans fell silent.

Perhaps President Reagan’s campaign aides failed to tell him who his audience was that day. What Reagan clearly didn’t understand was that the Charlotte community took enormous pride in the integrated schools that busing had produced. Former Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools Superintendent Dr. Jay Robinson – the first president of the Public School Forum of North Carolina – was quoted in news reports at the time: “[Reagan] was met with dead silence. What happened in Charlotte became a matter of community pride.”

The next day the Charlotte Observer published an editorial entitled, “You Were Wrong, Mr. President.” The editorial board rebuked the president in a powerful statement in support of school desegregation, writing, “Charlotte-Mecklenburg’s proudest achievement of the past 20 years is not the city’s impressive skyline or its strong, growing economy. Its proudest achievement is its fully integrated schools.”

Fast forward 34 years. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools most recent actions in response to efforts by four predominantly white suburban communities to potentially create and fund new charter schools for its own residents have been met with criticism, not support, by the Charlotte Observer editorial writers. That’s got me scratching my head.

CMS passed a resolution to block new school construction in Matthews, Mint Hill, Cornelius and Huntersville unless the communities agreed to a moratorium on creating these municipal charter schools in those towns. It hardly seems unreasonable for CMS to carefully consider new investments of scarce construction dollars in areas that may no longer want to be part of the district.

Could the school board have handled things better? Given the passion and heated rhetoric on both sides, more caution was probably warranted before taking this bold public step. But should that really be the point?

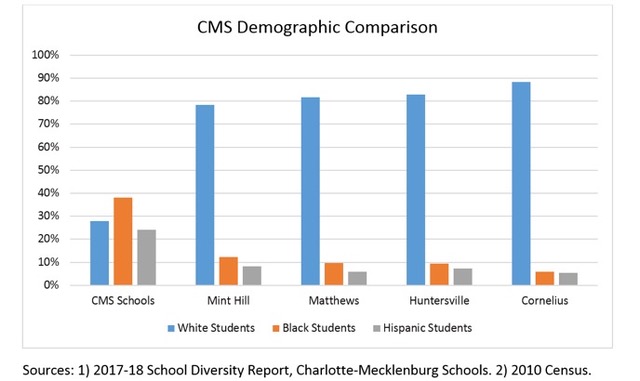

Thanks to House Bill 514 introduced by Rep. Bill Brawley, if these four communities move forward and create their own separate charter schools with preferential admittance of town residents, it will exacerbate segregation. Regardless of intent, that will happen. The populations of Huntersville, Cornelius, Matthews and Mint Hill are on average 80% White, 10% Black and 6% Hispanic. The current CMS student population is 29% white and 40% black and 22% Hispanic. These potential new charter schools will be hyper-segregated and white while CMS will conversely become even more black and brown, taking another huge step backward on efforts to ensure Charlotte’s schools are integrated.

For many years, Charlotte was known across the country as “the city that made desegregation work.” Charlotte, after all, was the site of the 1971 Supreme Court decision in Swann v. Charlotte Mecklenburg Board of Education, which led to the implementation of a large, district-wide busing plan to finally put into practice what Brown v. Board of Education had ordered (but southern districts had resisted) over 15 years earlier. Despite significant backlash, black and white community leaders, parents, and administrators worked together to draw up a plan to ensure that the racial makeup of district schools was reflective of those of the community overall; and for the most part, it worked.

Research by UNCC professor Roslyn Mickelson and others have shown that between 1971 and 2002, the majority of CMS students attended racially desegregated schools and achievement for all students improved as a result. Of course, desegregation did not rid Charlotte of its deep, historical racial inequalities, but it was a step in the right direction on a long journey.

Now Charlotte is making headlines again in conversations about school segregation–but this time, not for accolades. In 2001, after a white parent sued the school district on the grounds that its race-conscious school assignment policy was discriminatory towards white students, a Reagan appointed judge, Robert Potter, declared that CMS had declared “unitary” status, and could no longer use race as a factor in student assignment.

As a result, segregation increased almost immediately to levels close to what it had been before Swann. Today more than 20% of CMS schools are more than 90 percent minority, compared to 0.1% in 1989. A rise in charter school enrollment has further fueled resegregation, as these schools tend to be much more racially isolated than traditional public schools.

Today, the city that made desegregation work is the most segregated school district in North Carolina. The creation of exclusive municipal charter schools will only make matters worse in Charlotte. We urge Charlotte’s powerful corporate, philanthropic and media voices that championed desegregation efforts in the past to focus on the likely long-term devastating impact of these new municipal charter schools and less on personalities and school board actions. Isn’t it time to find some inspiration from the city’s noble history and save the outrage for any efforts to take Charlotte backwards?

Keith Poston is president and executive director of the Public School Forum of North Carolina, a nonpartisan, nonprofit organization focused on public education in North Carolina.

Leave a Reply