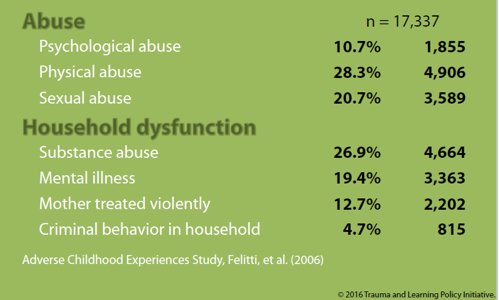

Childhood trauma is an all-too common factor in the lives of students. The CDC-Kaiser Permanente Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study, conducted from 1995-1997, documented the prevalence of traumatic experiences in childhood. Among respondents, 28% were physically abused as children; 21% were sexually abused; 27% lived in households where substance abuse occurred; and 13% lived in homes where the mother was treated violently (see figure at right).((Figure reprinted from Massachusetts Trauma and Learning Policy Initiative, Presentation to Study Group XVI, February 3, 2016. Data from Felitti, V. J., et al. (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The adverse childhood experiences (ACE) study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14(4), 245-258.)) One in five children experienced traumatic events in three or more categories of ACEs.((Anda, R. F., et al. (2006). The enduring effects of abuse and related adverse experiences in childhood. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci, 256, 174-186.))

Childhood trauma is an all-too common factor in the lives of students. The CDC-Kaiser Permanente Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study, conducted from 1995-1997, documented the prevalence of traumatic experiences in childhood. Among respondents, 28% were physically abused as children; 21% were sexually abused; 27% lived in households where substance abuse occurred; and 13% lived in homes where the mother was treated violently (see figure at right).((Figure reprinted from Massachusetts Trauma and Learning Policy Initiative, Presentation to Study Group XVI, February 3, 2016. Data from Felitti, V. J., et al. (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The adverse childhood experiences (ACE) study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14(4), 245-258.)) One in five children experienced traumatic events in three or more categories of ACEs.((Anda, R. F., et al. (2006). The enduring effects of abuse and related adverse experiences in childhood. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci, 256, 174-186.))

Responses to traumatic experiences affect whether students are able to engage productively in social contexts. Though students can display remarkable resilience in the face of adversity, experiences of trauma can also shape brain development and behavior in ways that inhibit success in school and lead to negative academic and life outcomes.

Too often, students arrive at school too overwhelmed to learn. Their neurological systems are besieged by their responses to adverse experiences, as high levels of stress hormones over prolonged periods cause chemically toxic effects on regions of their brains that deal with problem-solving and decision-making.((De Bellis, M. D., & Zisk, A. (2014). The biological effects of childhood trauma. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 23(2), 185-222.)) Educators see ACEs manifest in negative and disruptive behavior, but often this is a result of students functioning in a constant state of hypervigilance to danger or perceived threat. ACEs and their consequent effects on brain functioning may provoke a trauma response that causes students to “fight” (engage in violence or aggression), “take flight” (absenteeism; dropouts), or “freeze” (shut down; withdraw).

Schools and school systems typically focus on behavior itself, instead of scrutinizing and responding to aspects of students’ experiences that shape their behavior. Too often, teachers and school leaders respond to misbehavior by asking, “what’s wrong with you?,” when instead they should be asking, “what happened to you?” The result is to punish or disengage from students at their most vulnerable moments, when they are most in need of understanding, support, and help in building new coping skills.

Study Group XVI’s Committee on Trauma & Learning examined the incidence of traumatic childhood experiences, learned about the potential effects of those experiences on developing children’s brains, reviewed research connecting the dots between neuroscience and student learning and behavior, and considered what the links between traumatic events, brain responses, and the resulting effects on students mean for schools.((This summary of committee activity includes portions of the narrative from a Public School Forum i3 Development Grant application that aims to operationalize several of the Committee’s recommendations.)) Our recommendations draw on the available research to develop strategies to help educators engage more productively with traumatized students. The research portends that traumatized children will act out, withdraw, or avoid uncomfortable situations altogether (“fight, flight, or freeze”). Understanding the root causes of these reactions can help school-based professionals and partners from other fields create safe and supportive learning environments to help students manage their experiences and engage more fully and successfully in school.

- Trauma-sensitive practices in Buncombe County Schools with David Thompson, Director of Student Services for Buncombe County Schools. Mr. Thompson met with the Committee to share lessons that his district has learned as they have instituted a district-wide approach called Compassionate Schools to deal with the impact of ACEs on learning. The Buncombe County initiative uses a framework from Washington State, called The Heart of Teaching and Learning.((Wolpow, R., Johnson, M., Hertel, R., & Kincaid, S. (2016). The heart of learning and teaching: Compassion, resiliency, and academic success. Olympia, WA: Washington State Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction.)) Thompson spoke of the need to shift student and teacher mindsets from trauma to resiliency. In a related article for EdNC, Thompson wrote that based on research on changes in brain chemistry resulting from chronic stress or trauma, “[we] can conclude that many of the behaviors teachers and administrators consider most disruptive and maladaptive in the school environment are simply coping and survival strategies that are very much brain-based behaviors.”((Thompson, D. (2016). “Building resilient children by creating Compassionate Schools.” EdNC. https://www.ednc.org/2015/12/15/building-resilient-children-creating-compassionate-schools/))

At the time of his presentation to the Committee, Buncombe County had trained staff at 13 of their 26 elementary and middle schools on trauma-sensitive practices, with the remainder to be trained in the following 18 months. Thompson emphasized the need to build resiliency through existing tiered intervention models such as PBIS, which are data-driven and already in place in many schools. The advantage of a tiered approach is that all students receive some support in building social-emotional skills, which contributes to a positive climate with a shared set of skills and expectations. Student at higher tiers—those with moderate to severe challenges—receive additional supports to address their needs, including through collaboration with providers outside the school setting.

At the time of his presentation to the Committee, Buncombe County had trained staff at 13 of their 26 elementary and middle schools on trauma-sensitive practices, with the remainder to be trained in the following 18 months. Thompson emphasized the need to build resiliency through existing tiered intervention models such as PBIS, which are data-driven and already in place in many schools. The advantage of a tiered approach is that all students receive some support in building social-emotional skills, which contributes to a positive climate with a shared set of skills and expectations. Student at higher tiers—those with moderate to severe challenges—receive additional supports to address their needs, including through collaboration with providers outside the school setting.

The Buncombe County initiative emphasizes the importance of culture change in creating and advocating for trauma-sensitive schools, including through partnership with community agencies. Buncombe County created an ACEs subcommittee consisting of over 30 agencies, including health care providers, the North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services, mental health providers, law enforcement, and numerous education groups. All of these stakeholders worked together with the district and schools to develop resources, host a regional ACEs Summit, and find opportunities to support the local schools in their Compassionate Schools work. Taken together, these approaches have resulted in a community of professionals and caregivers who understand the impacts of trauma, recognize effective approaches to building resilience, and consistent with ESSA, are working collaboratively to support the success of each child across all areas of their lives.

- Trauma & Learning Policy Initiative with Michael Gregory and Joel M. Ristuccia. The Massachusetts-based Trauma & Learning Policy Initiative (TLPI) works to ensure that children traumatized by exposure to violence and other adverse childhood experiences succeed in school. Gregory and Ristuccia discussed major strands of TLPI’s activity in individual student advocacy, school-based trauma-sensitive pilot programs, and policy advocacy. They spotlighted five cornerstones of their work:

1. Many students have had traumatic experiences.

2. Trauma, which is a response to adversity, can impact learning, behavior, and relationships at school.

3. Trauma-sensitive schools help children feel safe so they can learn.

4. Trauma sensitivity requires a whole-school effort.

5. Helping traumatized children learn should be a major focus of education reform.

TLPI defines a “trauma-sensitive school” as “[a school] in which all students feel safe, welcomed, and supported, and where addressing trauma’s impact on learning is at the center of its educational mission.” The “whole-school effort” TLPI advocates for is a framework for educators to weave trauma sensitivity into all that they do. Elements of the framework focus on leadership, professional development, access to resources, and collaboration with families. Gregory and Ristuccia provided an overview of a two-volume publication, Helping Traumatized Children Learn, that can assist school teams in becoming trauma-sensitive and help state and local leaders craft policies to support them.

- Studies on the prevalence of ACEs and their neurological impact. Numerous studies show that a significant number of children experience ACEs.((Anda et al. (2006); Felitti et al. (1998); Saunders, B. E., & Adams, Z. W. (2014). Epidemiology of traumatic experiences in childhood. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 23(2), 167-184.)) Many of these children experience multiple traumatic events during childhood, and the cumulative exposures result in the development of a trauma response, with more ACEs resulting in increasingly severe levels of harm to brain structures and functions.((Anda et al. (2006).))

- Literature on the impact of the trauma response on brain development, behavior, and learning. An emerging body of research is revealing important insights about how early adverse experiences and the resulting trauma response can affect brain development, behavior, and learning.((Shonkoff, J. P., et al. (2011). The lifelong effects of early childhood adversity and toxic stress. Pediatrics, 129(1), e232-e246.)) Advances in scientific research shed considerable light on neurobiological consequences of violence and trauma,((Bevans, K., Cerbone, A., & Overstreet, S. (2005). Advances and future directions in the study of children’s neurobiological responses to trauma and violence exposure. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 20(4), 418-425.)) and the new field of “developmental traumatology” examines psychiatric and psychobiological effects of chronic stress on the developing child.((De Bellis, M. D., & Zisk, A. (2014). The biological effects of childhood trauma. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 23(2), 185-222.)) Studies in the social sciences demonstrate links between childhood trauma and behavior, showing how ACEs can underlie problematic behaviors that often manifest in classrooms.((Shonk, S. M., & Cicchetti, D. (2001). Maltreatment, competency deficits, and risk for academic and behavioral maladjustment. Developmental Psychology, 37(1), 3-17; Greenwald O’Brien, J. P. (1999-2000). Impacts of violence in the school environment: Links between trauma and delinquency symposium: Creating a violence free school for the twenty-first century: Panel two: Family and community responses to school violence. New England Law Review, 34, 593-600.)) Likewise, research finds direct links between ACEs and learning, including cognitive, academic, and social-emotional outcomes.((Perfect, M., Turley, M., Carlson, J., Yohanna, J., & Saint Gilles, M. P. (2016). School-related outcomes of traumatic event exposure and traumatic stress symptoms of students: A systematic review of research from 1990 to 2015. School Mental Health, 8, 7-43; Porche, M. V., Costello, D. M., & Rosen-Reynoso, M. (2016). Adverse family experiences, child mental health, and educational outcomes for a national sample of students. School Mental Health, 8(1), 44-60.))

- Research linking ACEs to negative academic and life outcomes. Research has shown that students who experience three or more ACEs score lower than their peers on standardized texts; are 2.5 times more likely to fail a grade; are placed in special education more frequently; and are more likely to be suspended and expelled.((Wolpow et al. (2016).)) Children exposed to traumatic events show more post-traumatic stress reactions that impact their ability to function effectively in schools and other social settings.((Alisic, E., Van der Schoot, T. A., Van Ginkel, J. R., & Kleber, R. (2008). Looking beyond PTSD in children: Posttraumatic stress reactions, posttraumatic growth, and quality of life. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 69, 1455-1461; DeBellis, M. D., & Thomas, L. A. (2003). Biologic findings of post-traumatic stress disorder and child maltreatment. Current Psychiatry Report, 5, 108-117.; McLaughlin, K. A., et al. (2013). Trauma exposure and posttraumatic stress disorder in a national sample of adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 52(8), 815-830 e14.)) In the long run, traumatic events and the trauma responses they elicit can lead to lower quality of life and a range of adverse mental and physical health outcomes.((Alisic et al. (2008); Kendall-Tackett, K. A., Williams, L. M., & Finkelhor, D. (1993). Impact of sexual abuse on children: A review and synthesis of recent empirical studies. Psychol Bull, 113, 164-180; Kendler, K.S., Bulik, C. M., Silberg, J., Hettema, J. M., Myers, J., & Prescott, C. A. (2000). Childhood sexual abuse and adult psychiatric and substance abuse disorders in women: An epidemiological and cotwin control analysis. Arch Gen Psychiatry, 57, 953-959; Osofsky, J. D. (1999). The impact of violence on children. Future Child, 99, 33-49; Putnam, F. W. (1998, Mar. 20). Developmental pathways in sexually abused girls. Presented at Psychological Trauma: Maturational Processes and Psychotherapeutic Interventions. Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA; van der Kolk, B. A., Perry, J. C., & Herman, J. L. (1991). Childhood origins of self-destructive behavior. American Journal of Psychiatry, 148, 1665-1671; Wolpow et al. (2016).)) Moreover, as the breadth of a child’s exposure to ACEs increases, so do multiple risk factors for several leading causes of death in adulthood.((Felitti et al. (1998); Anda et al. (2006).))

- Research on the potential for interventions to ameliorate the negative impacts of trauma. There is considerable work on the resilience that can be built through positive classroom climate, nurturing teachers and other adult caregivers, and direct intervention and support for improving self-regulation and developing social-emotional skills. Pioneering programs are demonstrating the importance of creating and advocating for trauma-sensitive schools in order to help students build these assets and improve their long-term trajectories.((E.g., Wolpow et al. (2016); Cole, S., Eisner, A., Gregory, M., & Ristuccia, J. (2013). Helping traumatized children learn: Creating and advocating for trauma-sensitive schools. Boston, MA: Massachusetts Advocates for Children.))

Through meetings with experts and review of relevant resources, Committee members realized that many educators are not aware of the profound effects trauma and stress have on the brain—an understanding that is critical for responding to students’ behaviors and emotions. While educators have a strong appreciation of the importance of forming relationships with students, helping them develop a deeper knowledge of ACEs and their potential impact on brain chemistry can help create a sense of urgency around implementing trauma-sensitive practices. This heightened awareness can change their perspectives on (and increase their empathy for) their most challenged students, and can help them support these students in building skills rather than punishing them and exacerbating negative spirals.

Recommendation 1. Maximize impact of opportunities under the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) to support practices that recognize the impact of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) on learning.

Section 4108 of the Every Student Succeeds Act requires every district that receives funds under Title I, Part A to use a portion of its funds to foster safe and supportive school environments. Options for meeting this requirement include programs, services, supports, and staff development based on evidence-based, trauma-informed practices, and training for school personnel in effective and trauma-informed practices in classroom management. District officials should strongly consider the inclusion of these options as part of a comprehensive approach to meeting the needs of their most vulnerable students. Other education-focused organizations may have roles to play in preparing guidance for districts about how to maximize the impact of these activities. Field leaders in other states—including the Compassionate Schools Initiative in Washington state and the Massachusetts Trauma & Learning Policy Initiative, as well as North Carolina pioneer Buncombe County Schools—can serve as sources of model programs and materials, as well as thought partners in new program design.

In addition, under Sections 2102 and 2103 of the Act (Title II, Part A), states may use federal funds provided through formula grants for supporting effective instruction to carry out in-service training for school staff to help them understand when and how to refer students affected by ACEs for appropriate treatment and intervention services. Permissible uses for these funds also include a variety of options that support education professionals in recognizing and addressing the specific needs of vulnerable students.

These sections of the federal law place identifying and addressing childhood trauma and other variables linked to poverty alongside policy options for recruiting and retaining effective teachers and school leaders, maximizing the impact of early childhood education, using data to improve student achievement, and serving students with disabilities. This inclusion parallels the recommendations of the Equity and Excellence Commission’s report, signaling that children’s experiences with poverty have taken their place alongside other significant variables impacting student achievement in the federal education policy framework.

Finally, maximizing the opportunity under ESSA to address the impact of adverse childhood experiences on student learning will require thoughtful development of North Carolina’s state ESSA plan, which the Department of Public Instruction is now crafting and will submit by March 2017. Each state is required to develop its own plan to comply with the new federal law and address issues including school accountability, student assessment, support for struggling schools, and other issues. Expanded state authority in this new era in federal policy, and the focus on the whole child within the federal legislation, make this the perfect moment to intentionally address the issue of childhood trauma in development and implementation of a comprehensive state plan. The other recommendations below provide options for state policy and programmatic interventions that can help teachers and other school-based professionals recognize and respond to the behavioral manifestations of trauma and other impacts of ACEs on learning.

Recommendation 2. Design “on-ramps” for educators to increase awareness of ACEs, their impact on learning, and appropriate interventions.

Deep understanding of this topic is a new phenomenon, steeped in recent neuroscience research and a young body of evidence on effective school-based practices and high-impact partnerships between schools and other child-serving professionals and institutions. As a result, DPI, districts, and external partners should design and offer trainings and conferences like the 2015 Adverse Childhood Experience Southeastern Summit in Asheville. These opportunities allow education professionals to become well-versed in the relevant research, discuss the impact of that research on teaching and learning, and collaborate to develop strategies to improve their responses to ACEs in their schools.

School systems might utilize badges or other credentials for the completion of training in this area, and might even open the trainings to other categories of professionals likely to interact with vulnerable students (e.g., juvenile defenders, nurses, judges, and law enforcement). Training might be differentiated based on teachers’ levels of awareness or experience with ACEs. Statewide or regional events would be an excellent way to share experiences and resources across systems in this new and rapidly evolving area. DPI, consortia of districts, or external partners could create resource databases or clearinghouses for information about ACEs and their impact on student learning. Finally, these groups should also work closely with the state’s teacher and school leader preparation programs to influence their training of future education professionals. Educator training should include a concerted focus on the impact of poverty-linked variables and ACEs on learning, along with effective strategies at the state, district, school, and classroom levels to mitigate ACEs impact and support student success.

Recommendation 3. Implement and evaluate pilot programs, and share data and related resources.

Districts should consider creating pilot programs to transform the culture at high-need schools to help them become trauma sensitive, potentially utilizing the whole-school, inquiry-based process and related tools contained in the resource, Creating and Advocating for Trauma-Sensitive Schools. Such programs offer excellent opportunities for integrated approaches through partnership between schools and health care providers, law enforcement, and other institutions that together can better understand and address the impacts of ACEs on students.

Because the process of implementing such a program and related partnerships can be a time-consuming endeavor with associated planning and implementation costs (materials, teacher stipends, etc.), schools and external partners should seek state, district, or private funding to support pilot programs. Districts and funders looking at potential pilot sites should consider the readiness of school-based professionals and partners to undertake such a process. Pilot programs should involve researchers in their design and all stages of implementation to capture key data that can guide improvement and support program replication or expansion, if successful. All pilot programs should be driven by and involve significant buy-in from school-based actors, supported by coaches or other partners to support learning and planning around trauma-sensitive approaches. This approach is preferable to programs that merely regard schools as physical sites for outside actors’ service provision. Only with the intimate involvement of teachers and school leaders can schools become strong partners in the identification of ACEs, timely referral for appropriate services, and productive responses within educational settings.

Recommendation 4. Create statewide policy to guide schools’ work addressing the impacts of ACEs on learning.

Oregon House Bill 4002 (2016) and Massachusetts House Bill 4376 (2014) are models for statewide frameworks addressing the impact of ACEs on student learning. The Oregon bill establishes a pilot program to use trauma-informed practices in schools, utilizing national models and coordinating school-based resources (school health centers, nurses, counselors, and administrators) with the efforts of coordinated-care organizations, public health, nonprofits, the justice system, businesses, and parents. The bill authorizes $500,000 for the state’s three-year pilot, which will be overseen by “trauma specialists” in schools and bolstered by a strong research model in place from the beginning to evaluate the pilot and help the state apply lessons learned in the future.

The Massachusetts policy requires the development of a statewide Safe and Supportive Schools Framework; provides a self-assessment tool to help schools create action plans; and encourages schools to incorporate action plans into their school improvement plans. Massachusetts also funded a grant program ($200,000) to support pilot programs as models for creating safe and supportive schools. Finally, the law creates a commission to assist with statewide implementation of the framework and make recommendations for additional legislation.

We recommend the creation of a Task Force to examine these state laws and other, similar policies, and to consult with appropriate national experts, to determine an appropriate suite of state policy interventions for consideration by the General Assembly, the State Board of Education, DPI, and local boards of education and district officials. The Task Force should publish its recommendations to encourage the development of state and local policy that supports the movement toward creating trauma-sensitive schools across the state. The Task Force should also recommend sources of funding for this work, including state funding but also appropriate private foundations in education, health care, and other sectors who might support programmatic and policy interventions on this subject.

To carry these recommendations forward, the Public School Forum recently formulated the North Carolina Safe and Supportive Schools Initiative, a partnership of the Forum and six North Carolina LEAs (Asheville City Schools, Rowan-Salisbury Schools, Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools, Winston-Salem/Forsyth County Schools, Edgecombe County Schools, and Elizabeth City-Pasquotank Public Schools). The Initiative will utilize two action strategies: 1) educator training to increase understanding of adverse childhood experiences, the potential trauma response in children, and the resulting impacts on student learning and behavior, and to introduce short- and long-term interventions that can restore students’ sense of safety and agency, and 2) structured pilot programs in partner LEAs to create inclusive learning environments that build student resiliency as an alternative to removing students from classrooms.

[…] Committee on Trauma & Learning. Research has documented the high prevalence of traumatic experiences in childhood, particularly among students living in poverty. This Committee studied the prevalence and impact of these experiences on student learning, and learned from state and national experts about strategies for addressing these impacts within educational settings. The Committee recommends the following: […]