Study Group XVI’s second committee focused explicitly on how race affects student outcomes in North Carolina, and the equity issues implicated by the effects. Committee members sought to better understand critical areas where race correlates with educational opportunity in ways that diminish the likelihood of success for students of color, and to develop solutions that will lead to improved academic and life outcomes for these students.

The social and historical roots of race run deep in our nation and state. Within education these roots are entangled in a complex interplay with the topics taken up by the study group’s other two committees: childhood trauma and low-performing schools. Racial equity is a topic many education groups have been hesitant to tackle, for fear of stirring up controversy, or worse. But the dearth of robust discussion of race, coupled with the obvious and unrelenting space it occupies in many of the persistent inequities in our state’s education system, convinced us that any exploration of educational opportunity that did not address issues of race head-on would be incomplete.

Throughout the study group, the committee employed rigorous analysis of research and data on racial equity, using the best available evidence to guide its observations and recommendations. The complexities of race–in both its social construction and its legal codification–mandated the use of a multifaceted approach to developing common understanding and generating responsive policies and programs. The candid focus on race allows for honest discussion and assessment of the problem. To that end, the committee approached its task by learning from experts in education, law, and sociology, who helped committee members piece together a complex puzzle built from pieces including the following:

- A North Carolina-specific historical narrative on race

- A systems-level analysis of the racial gaps that exist across various institutions

- Insights from members of a small collective seeking racial equity in a local district

- Statewide racial data from the North Carolina Department of Public Instruction

- An analysis of the structural underpinnings of racialized outcomes by a renowned sociologist.

Committee members then processed these learnings together in intensive work sessions, with stakeholders from across the state working collaboratively to qualify definitions, share case studies, and contemplate solutions

- The History of Educational Opportunity with Ann McColl, an attorney at Everett Gaskins Hancock, LLP practicing in the field of education law. She is the author of Constitutional Tales, an intensive research effort exploring the historical foundations of the North Carolina constitution and development of public schools.((McColl, A. (2010). Constitutional Tales. Retrieved August 29, 2016, from https://constitutionaltales.org/)) McColl is an unparalleled expert on the racial dimensions of early public education in our state and how a deliberate “disfranchisement” campaign influenced the formation of the institution.((Governor Aycock on “the negro problem” (n.d.). Retrieved August 29, 2016, from https://www.learnnc.org/lp/editions/nchist-newsouth/4408)) She provided a historical analysis, full of rare primary sources and remarkable quotes that exposed a long sordid chronicle of intentional inequities from our collective past.((McColl, A. (2015, October 29). Moving past intentional inequities in education – EducationNC. Retrieved August 29, 2016, from https://www.ednc.org/2015/10/29/moving-past-intentional-inequities-in-education/)) She argued that these injustices reach into our present and hold sway over many of the forces resulting in our current educational inequities.

- Measuring Racial Equity: A “Groundwater” Approach with Deena Hayes-Greene of the Racial Equity Institute (also one of our Committee co-chairs). Pulling from a bevy of state and national studies, Hayes-Greene identified several key observations about the nature of racial inequity: 1) Racial inequity looks the same across systems (education, health care, banking, etc.), 2) Socio-economic difference does not explain racial inequity, 3) Systems contribute significantly to disparities, 4) The systems-level disparities cannot be explained by a few ‘bad apples’ or ill-intentioned gatekeepers, 5) Inequitable outcomes are concentrated in certain geographic communities, and 6) Analysis that includes race draws starkly different conclusions than analysis that does not. Hayes-Greene used these observations to liken racial inequity to “groundwater” contamination that spreads and pollutes the land and nearby bodies of water. Education is just one sector with racial disparities, but the same root causes affect outcomes in health care, criminal justice, child welfare, banking, housing, employment, and other areas of society.

- Excellence with Equity: The Schools Our Children Deserve with The Campaign for Racial Equity in Chapel Hill-Carrboro Schools. The Campaign for Racial Equity is a growing movement of community members and stakeholders in Chapel Hill-Carrboro concerned about racial inequity.((Schultz, M. (2015, October 28). Group wants end to Chapel Hill-Carrboro achievement gap. Retrieved August 29, 2016, from https://www.newsobserver.com/news/local/community/chapel-hill-news/article41748738.html)) Representatives from the Campaign presented to the Committee about the development of their community movement. It began as a response to several indices of a climate and culture of racial disadvantage within the district. With a leadership network of community members from diverse backgrounds and perspectives, they set about creating an action plan for how to address racial equity that included focusing on school board elections, researching and writing a report on responding to racial inequity, and meeting with the administration and school board to discuss findings within the report. In producing the report, the Campaign for Racial Equity consulted critical district data, held listening sessions with community members, researched exemplar schools and practices, applied racial equity analysis to data, and produced recommendations.((Excellence with Equity: The Schools Our Children Deserve (Rep.). (2015, October 23). Retrieved August 29, 2016, from The Campaign for Racial Equity in Our Schools website: https://chapelhillcarrboronaacp.files.wordpress.com/2014/05/excellence-with-equity-report-final10-23.pdf )) The report culminated in eight equity goals the Campaign hoped to see embraced by the school system.((Ibid))

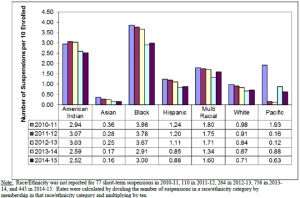

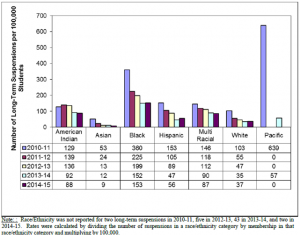

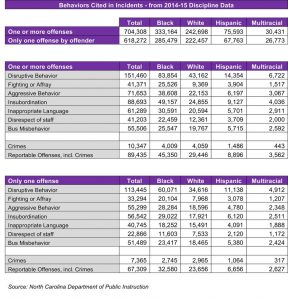

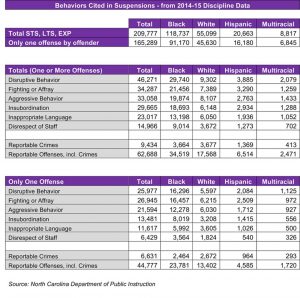

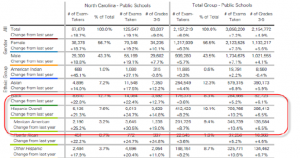

- Gaps in Student Achievement in North Carolina on Selected Variables with Dr. Lou Fabrizio, Director of the Division of Data, Research and Federal Policy at the North Carolina Department of Public Instruction. Dr. Fabrizio and his team presented a comprehensive picture of the state of racial equity in NC public schools. The presentation provided extensive data disaggregated by race, gender, economic disadvantage, limited English proficiency (LEP), and disability. Areas of Dr. Fabrizio’s presentation included the National Assessment of Education Progress (NAEP), End-of-Grade (EOG) and End-of-Course (EOC) Assessment, ACT, Advanced Placement (AP), cohort graduation rates, short-term and long-term suspensions and expulsions, teacher effectiveness ratings, the State Educator Equity Plan, and selected additional references and research studies.((Fabrizio, Lou. “Gaps In Student Achievement In North Carolina On Selected Variables”. 2016. Presentation. https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B6WgyOVA1ZEhSWxKOFFERExEaXM/view?usp=sharing)) A major, recurring theme in the data was the relatively low performance of Black, Hispanic and American Indian compared to their white and Asian counterparts, and the disproportionate representation of these groups in the area of student discipline.

Watch Lou Fabrizio and Dr. Angel Harris Presentations

Part 1

Part 2

Copy of Lou Fabrizio’s presentation

- Educational Disparities: Perspective from One Sociologist with Dr. Angel Harris, Professor of Sociology at Duke University and Director of the Program for Research on Education and Development of Youth (REDY). Dr. Harris is a prominent sociologist who has written and lectured extensively on the racial achievement gap. His book Kids Don’t Want to Fail deals with the “oppositional culture” theory of why black students underperform, while his text Broken Compass challenges the notion of parental involvement as an indicator of academic performance. Dr. Harris juxtaposed the ideas of social structure and personal agency when discussing gaps in academic achievement between students of color and their white counterparts. He asserted that we have failed to appreciate the racial achievement gap for what it really is: a byproduct of a much larger gap in opportunity. This lack of understanding explains why gap convergence has stalled in recent years despite massive efforts like No Child Left Behind. He argues we are in need of a new model of education that moves beyond superficial discussions about race and addresses it systemically. Approaches should be based on empiricism and strategies proven to increase achievement, not what is convenient or comfortable.

The Committee divided its work into seven domains derived from preliminary research of national trends in race and education and utilized as frames when studying North Carolina. The following section summarizes the committee’s core findings in each domain:

1. Resegregation

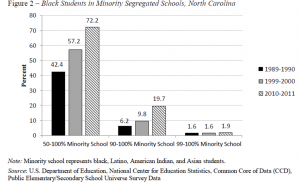

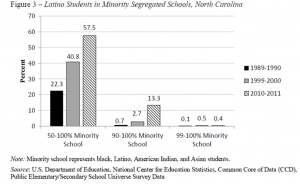

Although substantial progress was made in the desegregation of schools in the years following the landmark Supreme Court decision, Brown v. Board of Education (1954), North Carolina has several districts that have since resegregated, and others that never fully desegregated after Brown.((Ayscue, J. B., Siegal-Hawley, G., B. W., & Kucsera, J. (2014, May 14). Segregation Again: North Carolina’s Transition From Leading Desegregation to then Accepting Segregation (Working paper No. 6). Retrieved August 31, 2016, from The Civil Rights Project/Proyecto Derechos Civiles website: https://civilrightsproject.ucla.edu/research/k-12-education/integration-and-diversity/segregation-again-north-carolina2019s-transition-from-leading-desegregation-then-to-accepting-segregation-now/Ayscue-Woodward-Segregation-Again-2014.pdf)) Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools, once a national model for school integration efforts after Swann v. CMS (1971) has found itself with a large number of racially and socioeconomically isolated schools (a condition known as “double segregation”).((Ibid.))

Abandonment of desegregation efforts in favor of “neighborhood school” models has once again made schools more racially identifiable, due in part to residential segregation. For residents living in majority Hispanic and African American census blocks, the chance of their children attending racially-identifiable, high poverty, or low-performing schools is dramatically higher than for those in majority white census block.((The State of Exclusion: An Empirical Analysis of the Legacy of Segregated Communities in North Carolina (Rep.). (2013). Retrieved August 31, 2016, from UNC Center for Civil Rights website: https://www.uncinclusionproject.org/documents/stateofexclusion.pdf)) This backward trend can also be seen in Wake County, where racially and socioeconomically isolated schools have doubled in the past decade.((Hui, T. K., & Raynor, D. (2015, August 15). Wake County busing fewer students for diversity. Wake County Busing Fewer Students for Diversity. Retrieved August 31, 2016, from https://www.newsobserver.com/news/local/education/article31101236.html )) Over the past two decades, the share of Black and Hispanic students attending majority-minority and intensely-segregated schools statewide has grown significantly.((Ayscue et al., Segregation Again.)) Resegregation has appeared in other counties as well, including Guilford, Forsyth, Pitt, Halifax, and Harnett.

The trend toward resegregation is not limited to traditional public schools. North Carolina charters are increasing the extent to which the overall system of public education in the state is racially identifiable as well. Roughly two-thirds of all charter schools in the state are either disproportionately white or disproportionately students of color.((Ladd, H. F., Clotfelter, C. T., & Holbein, J. B. (2015, April). The Growing Segmentation of the Charter School Sector in North Carolina (Working paper No. 133). Retrieved August 31, 2016, from National Bureau of Economic Research website: https://www.nber.org/papers/w21078.pdf))

2. Discipline Disparities

Students of color in North Carolina schools have significantly higher rates of both short- and long-term suspensions than their white counterparts.((Report to the North Carolina General Assembly: Consolidated Data Report 2014-15 (Rep.). (2016, March 15). Retrieved August 31, 2016, from North Carolina Department of Public Instruction website: https://www.dpi.state.nc.us/docs/research/discipline/reports/consolidated/2014-15/consolidated-report.pdf)) The state has lowered the overall rates of suspension and expulsions over the past several years. What has not changed, however, is the disproportionate representation of students of color in disciplinary actions. Black students in particular are as much as four-times as likely to receive short-term suspensions as their white counterparts, with similar gaps in long-term suspension data. American Indians are suspended at rate three-and-a-half-times more.((Ibid.)) This disproportionality is appropriately labeled a “disparity” because similarly situated students of difference races are treated differently. Studies suggest that students of color are judged more harshly for subjective offenses (e.g. insubordination, disrespect, aggressive behavior, etc.), while white students receive punishment more for objective offenses (e.g. weapons, drugs, vandalism, etc.).((Skiba, R. J., Michael, R. S., Nardo, A. C., & Peterson, R. L. (2002, December). The Color of Discipline: Sources of Racial and Gender Disproportionality in School Punishment. The Color of Discipline: Sources of Racial and Gender Disproportionality in School Punishment, 34(4), 317-342. Retrieved August 31, 2016, from https://indiana.edu/~equity/docs/ColorofDiscipline2002.pdf)) The use of discretion in enacting student discipline appears to give rise to racially disparate impact.

3. Opportunity Gap

In nearly every educational metric, from cohort graduation rates to college and career readiness, the majority of students of color in North Carolina underperform their white counterparts.((Fabrizio, “Gaps in Student Achievement in North Carolina on Selected Variables.”)) The trend holds even when one controls for economic disadvantage, exceptional children’s status, and limited English proficiency. This is commonly called the “achievement gap,” but is perhaps better termed an “opportunity gap.” Research reveals a measurable relationship between race and a slew of other social factors that limit educational opportunity. A student is at a decided disadvantage if he lives in poverty, lacks stable housing or adequate healthcare, experiences food insecurity, is exposed to adverse childhood experiences, has limited English proficiency, or is an undocumented immigrant. Students of color are overrepresented in these categories, all of which have deleterious effects on academic achievement.((Jiang, Y., Ekono, M., & Skinner, C. (2015, January). Basic Facts about Low-Income Children Children 12 through 17 Years, 2013 (Fact Sheet). Retrieved August 31, 2016, from National Center for Children in Poverty website: https://www.nccp.org/publications/pdf/text_1099.pdf)) As such, it is impossible to take any of these issues fully into account without acknowledging the resulting racially disparate impact.

4. Overrepresentation in Special Education

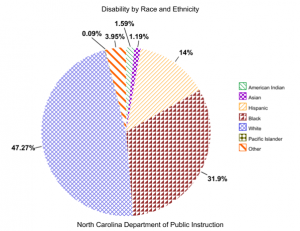

On a national scale, students of color have historically been overrepresented in special education.((Rebora, A. (2011, October 12). Keeping Special Ed in Proportion [Web log post]. Retrieved August 31, 2016, from https://www.edweek.org/tsb/articles/2011/10/13/01disproportion.h05.html)) In North Carolina, all racial subgroups remain relatively proportionately represented, with the exception of African Americans, who make up 26 percent of all public schools students yet comprise 32 percent of all school-aged children with disabilities. Specific areas where they are most overrepresented are: intellectual disability (45%), emotional disturbance (44%), developmental delay (34%), and specific learning disability (32%).((Report of Children with Disabilities (IDEA) Ages 6-21. (2016). Unpublished raw data. North Carolina Department of Public Instruction.)) These also tend to be the areas that are most stigmatizing.((Greenhouse, J. (2015, July 28). The Complicated Problem Of Race And Special Education [Web log post]. Retrieved August 31, 2016, from https://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/racism-inherent-in-special-education-leads-to-marginalization_us_55b63c0ae4b0224d8832b8d3)) Research in this area suggests that overrepresentation in these categories belies misdiagnosis rooted in cultural bias and misunderstanding.((Kanaya, T., & Ceci, S. (2009, December 23). Misdiagnoses of Disabilities. Retrieved August 31, 2016, from https://www.education.com/reference/article/misdiagnoses-of-disabilities/))

5. Access to Rigorous Courses and Programs

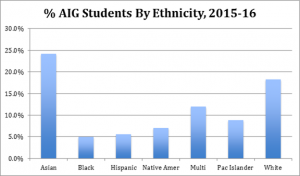

Students of color are underrepresented in the most rigorous courses and programs offered in North Carolina schools, including Advanced Placement (AP), International Baccalaureate (IB), and Academically or Intellectually Gifted (AIG). Deeper analysis of available data spotlights areas of concern, but also reveals some promising trends. On the one hand, students of color lag behind their peers in AP course enrollment, exam-taking, and exam pass rate. But a concerted effort has been made to increase AP subgroup enrollment and test-taking in North Carolina. Student participation in AP courses among American Indian students increased by 45 percent last year. Among Black students it increased by 22.8 percent, and for Hispanic students it jumped 21.3 percent.((NEWS RELEASES 2015-16. (2015, September 4). Retrieved October 10, 2016, from https://www.dpi.state.nc.us/newsroom/news/2015-16/20150904-01)) Exam pass rates have also improved. In AIG identification, disparities persist, with Black and Hispanic students the most dramatically under-identified groups, both around 5 percent.(([DPI AIG Child Count 2015]. (2015, July). Unpublished raw data.)) While policy states outstanding abilities are present in all student populations, this doesn’t seemed to represented proportionately.

6. Diversity in Teaching

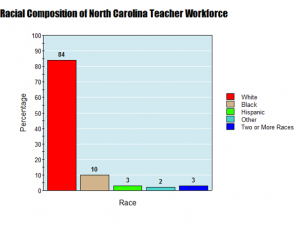

In North Carolina, the vast majority of the teaching force is white (84%).((Boser, U. (2014, May). Teacher Diversity Revisited (Issue brief). Retrieved July, 2016, from Center for American Progress website: https://www.americanprogress.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/TeacherDiversity.pdf)) This is a tremendous mismatch with an increasingly diverse student population that is half non-white. For the majority of teachers in the state it is likely that they will teach students who do not come from the same racial or ethnic background. Consequently, students in the state will not see themselves represented in the profession. Research has indicated that having teachers of color reduces the likelihood of suspension for students of color, leads to increased achievement, and increases identification as AIG.((Wright, A. C. (2015, November). Teachers’ Perceptions of Students’ Disruptive Behavior: The Effect of Racial Congruence and Consequences for School Suspension (Working paper). Retrieved August, 2016, from https://aefpweb.org/sites/default/files/webform/41/Race Match, Disruptive Behavior, and School Suspension.pdf & Grissom, J. A., & Redding, C. (2016). Discretion and Disproportionality: Explaining the Underrepresentation of High-Achieving Students of Color in Gifted Programs. AERA Open, 2(1). doi:10.1177/2332858415622175)) Additionally, it serves to decrease stereotypes for white students and promote cultural understanding. With enrollment in teacher preparation programs in decline, the challenge of filling classrooms with teachers of color and keeping them has become all the more crucial to help students of color succeed academically.

7. Culturally Responsive Pedagogy

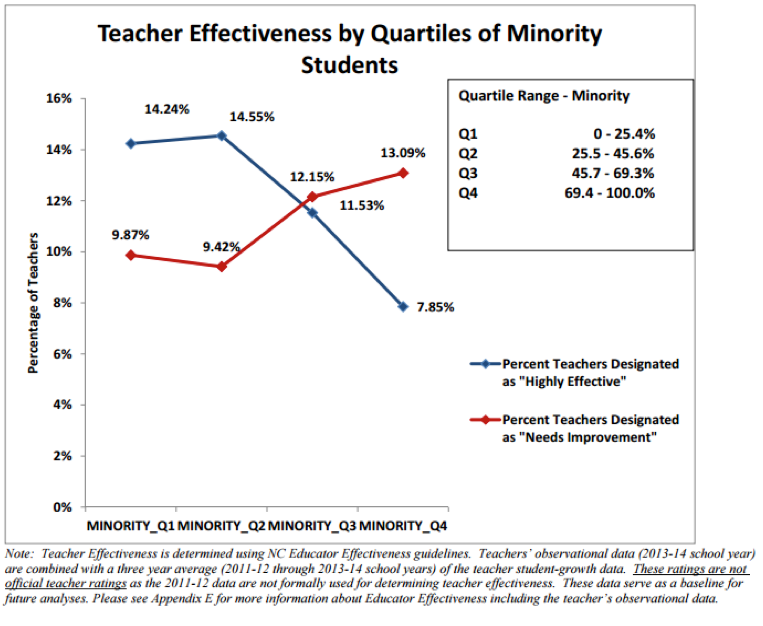

Teachers must be able to relate to the students they serve. Whatever their background, teachers need to understand their students both as individuals and as representatives of their communities. Unfortunately, recent North Carolina Teacher Effectiveness ratings for teachers instructing students of color have been dismal (see “Teacher Effectiveness by Quartiles of Minority Students”).((North Carolina’s State Plan to Ensure Equitable Access to Excellent Educators (Publication). (2015, November 15). Retrieved March, 2016, from https://www.dpi.state.nc.us/docs/program-monitoring/titleIA/equity-plan/equity-final.pdf. Submitted to U.S. Dept. of Education.)) This effectiveness rating is determined in part through observational data and three-year average student-growth.

Approaches to teaching that honor students’ cultural customs and traditions have been shown to increase achievement. On the flip side, a lack of cultural competence can have negative educational consequences. Underpinning many of the data disparities related to culturally responsive pedagogy is the presence of implicit racial bias. This refers to attitudes or stereotypes based on patterns and associations about racial groups that affect understanding, actions, and decisions in an unconscious manner. For school leaders and teachers alike, implicit racial bias can influence responses and decision-making on the job. Much research has been conducted in recent years on implicit racial bias and how it manifests itself even in the most well-intentioned individuals. Creating awareness about biases, and responding in ways that honor the culture of the student population, hold great promise to improve racial equity.

The intention of this report is to offer a thorough examination of racial inequity in North Carolina Public Schools, with a focus on generating feasible and plausible solutions to the problems. Members of the committee have dedicated themselves to actively researching the issues and scouring the regional and national landscape for exemplars. They have produced several recommendations focused on some level of policymaking: school, district or school board, and state.

It should be noted that some variation of the propositions contained herein may already be in place in specific districts or schools. In this case, it is our hope to expand on these ideas to create more widespread change throughout the state. The Public School Forum identified the need to lift race as a focal point of public education in the 2016 Top 10 Education Issues, and has already been in discussion with local education agencies seeking to address racial disparities. Additionally, we are represented on the Department of Instruction’s Discipline Data Working Group. But our earnest desire is to seek board-based change in the racially disparate outcomes within the state’s education system. We offer the following recommendations to achieve those ends:

Resegregation

1. Utilize socioeconomic integration models to diversify schools and prevent resegregation. Race and class are strongly correlated. As a result, policies that assign students to schools according to socioeconomic variables can also increase racial diversity. The Supreme Court has rejected student assignment policies based solely on race, but it has determined that promoting diversity and avoiding racial isolation are appropriate factors to consider in developing student assignment policy.((See Parents Involved in Community Schools v. Seattle School District No. 1, 551 U.S. 701 (2007).))

Wake County was one of the first systems in the nation to use this approach, and has been held up as a national model. Districts including Jefferson County Public Schools in Louisville, Kentucky, which had a racial quota in its assignment policy that was struck down by the Supreme Court, have remained integrated even without the option of race-based policies.((Semeuls, A. (2015, March 27). The City That Believed in Desegregation. The Atlantic. Retrieved February, 2016, from https://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2015/03/the-city-that-believed-in-desegregation/388532/)) Using a formula that takes into account household income, family composition, educational attainment of parents, and other factors, Jefferson County has managed to create one of the more racially diverse systems in the country, and its approach to diversity is widely credited with contributing to a thriving local economy.

According to a 2016 Century Foundation report, 91 districts and charter networks across the country have voluntarily adopted socioeconomics as a factor in the student assignment.((The Growth of Socioeconomic School Integration. (2016, February 09). Retrieved October 10, 2016, from https://tcf.org/content/facts/the-growth-of-socioeconomic-school-integration/)) This represents a growing trend among school systems seeking to promote diversity in student assignment and avoid racial isolation. Whereas some more rural or homogenous areas make this unattainable it should be pursued wherever possible.

2. Create citywide (non-neighborhood based) student assignment policies to curb residential segregation and eliminate racially-isolated geographic areas. The racial composition of certain neighborhoods within America’s cities is in large part an artifact of discriminatory practices. Through years of redlining, blockbusting, and steering by real estate agents, intentional residential segregation fostered racially monolithic parts of town.((Quick, K. (2016, March 23). The Myth of the “Natural” Neighborhood. Retrieved August, 2016, from https://tcf.org/content/commentary/11312/)) Against this backdrop, recent pushes for “neighborhood schools” may perpetuate or reinforce longstanding racial segregation.

School policy and housing policy are interdependent. Recent research suggests that if school systems take the lead in delinking neighborhoods from schools, the housing sector will follow and in turn become more racially diverse.((Siegel-Hawley, G. (2013, June). City Lines, County Lines, Color Lines: The Relationship between School and Housing Segregation in Four Southern Metro Areas. Teachers College Record, 115, 1-45.)) Furthermore, organizations like OneMECK (a Charlotte-based organization that focuses on ending policies and practices that lead to highly-concentrated poverty in schools and housing) work with city and county leaders to advocate for affordable housing and inclusionary zones to help break up poverty density in city neighborhoods, leading to increased diversity in schools.

Opportunity Gap

1. Adopt “community schools” models that leverage partnerships with service providers. School partnerships with providers that help meet critical needs of students and their families, can also help develop and sustain school-community connections.

In a community schools model, the school is not simply part of the community but central to it, becoming a hub for the identification of student and family needs and for the provision of services that help students engage productively in schools and family members provide needed support. For example, in Jennings, Missouri, Superintendent Tiffany Anderson successfully turned around a racially isolated, high poverty district by adopting a holistic approach that “[used] the tools of the school district to alleviate the barriers poverty creates.”((The Superintendent Who Turned Around A School District [Program]. (2016, January 3). NPR.)) In partnership with a nearby university, the school opened a clinic that offered mental health counseling, case management, and wellness education. The district also ran a food pantry for families, and provided training for teachers on the issues of institutional racism and poverty. This school is just one of many examples of utilizing partnerships to provide what schools cannot offer their students and families alone.((Welcome to the Coalition for Community Schools! (n.d.). Retrieved October 10, 2016, from https://www.communityschools.org/ & Kolodner, M. (2015, November 4). At a school in Brooklyn’s poorest neighborhood, literacy is up and disciplinary problems are down – The Hechinger Report. Retrieved October 10, 2016, from https://hechingerreport.org/at-a-school-in-brooklyns-poorest-neighborhood-literacy-is-up-and-disciplinary-problems-are-down/)) In Rowan-Salisbury Schools, the district tackled food insecurity over the summer by delivering meals to families utilizing a renovated bus — affectionately called “the Yum-Yum Bus.”((Hahn, N. (2016, August 31). One district is combatting summer hunger by going on the road. Find out how. – EducationNC. Retrieved October 10, 2016, from https://www.ednc.org/2016/08/31/one-district-combatting-summer-hunger-going-road-find/))

2. Create district equity departments with executive-level leadership. There are only a few districts in North Carolina that have prioritized equity, diversity or inclusion to the extent that they have dedicated this level of specific support for it. More than merely stating a goal or mentioning equity in a mission statement, districts must begin to operationalize their stated dedication to racial equity by placing district leaders in charge of elevating the issues, providing anti-racism training, monitoring data for racial disparities, and holding schools accountable for equity outcomes. Currently, there are fewer than 5 districts out of 115 in North Carolina that have such a dedicated department or leadership role. School boards also have a critical role to play in making racial equity part of their strategic plan and putting accountability measures in place for closing the various opportunity gaps.

Discipline Disparities

1. Require all schools and districts to publish annual discipline reports disaggregated by race with cross-tabulation. The State Board of Education should convene expert stakeholders to critique the categories of discipline data currently collected. The Board should also determine categorical designations for offenses to be tracked and published as part of the annual report, with an eye toward transparency and dissemination of meaningful data to the public. North Carolina is better than many other states in the level and depth of its consolidated discipline report, but schools and districts are not obligated to provide similarly nuanced information to their constituency.

A crucial objective of student discipline reports must be to help safeguard student rights by shining a light on areas of disproportionality or disparity as well as laud successes gained. At a minimum, discipline reports should include data on all significant disciplinary actions that list types of infractions (with specific and standardized definitions), track instructional time missed, and allow cross-tabulation and analysis of data by subgroup. This entails not only comparing students of different race, but also for instance black or Hispanic economically disadvantaged students to white non-economically disadvantaged students. Reports of this nature will go a long way toward earning the trust of communities of color by ensuring that trends and patterns will be analyzed to see which schools are moving toward more equitable student discipline practices. Guilford County School’s annual accountability report is an excellent template to follow.

2. Implement Restorative Justice and Positive Behavior Interventions & Supports (PBIS) as alternative and preventative measures of discipline. In recent years, as data has exposed racial disparities in student discipline, schools have been experimenting with alternatives to suspensions and zero tolerance policies. But decreasing gaps takes more than just a reduction in overall disciplinary actions. Restorative Justice programs like those in Oakland Unified School District have proven to be effective in decreasing the overall incidence of student misbehavior as well as reducing racial gaps.((Restorative Justice in Oakland Public Schools Implementation and Impacts (Rep.). (2014, September). Retrieved August, 2016, from Oakland Unified Public Schools website: https://www.ousd.org/cms/lib07/CA01001176/Centricity/Domain/134/OUSD-RJ Report revised Final.pdf)) Restorative Justice is not an alternative for disciplinary action but rather an intervention prior to escalation. It provides whoever committed the wrong the chance to be held accountable by the community of students affected, and it allows those individuals to determine what must be done to reconcile.

PBIS is a multi-level approach to dealing with student attitudes and behavior.((Positive Behavioral Interventions & Supports – OSEP. (n.d.). Retrieved July 12, 2016, from https://www.pbis.org/)) Its tiers focus on collective school-wide, classroom, and individual student-level supports. Data collected on PBIS should include data on race, since the behavioral intervention alone might alter disciplinary practices but not close gaps. On a broader level, Social-Emotional Learning (SEL) is a process that deals with emotional intelligence and helps students develop the competencies to identify and interpret their own emotions and the emotions of others, set and pursue goals, empathize, develop positive peer relationships, and learn how to self-regulate and interact effectively in social contexts.((Jones, S. M., Bouffard, S. M., & Weissbourd, R. (2013, May 1). Educators’ Social and Emotional Skills Vital to Learning: Social and Emotional Competencies Aren’t Secondary to the Mission of Education, but Are Concrete Factors in the Success of Teachers, Students, and Schools. Phi Delta Kappan, 62-65.)) Combined, these two approaches give schools a range of tools to help students learn appropriate learning behaviors through methods beyond punishment and push-out.

Overrepresentation in Special Education

1. Develop referral and initial evaluation process that take cultural differences into account when assessing students for disabilities. Students of color are overrepresented in the specific categories of special education that are deemed most “stigmatizing,” including intellectual disabilities, emotionally disturbances, and specific learning disabilities. Misidentification may be reinforced by stereotypes that people of color are intellectually inferior. Both the United States Department of Education and researchers have called for greater account of cultural differences in special education evaluation processes and interventions to address students’ special needs.((Ujifusa, A. (2016, February 23). “Rule for Identifying Racial Bias in Special Education Proposed By Ed. Department.” Education Week. Retrieved October 14, 2016 from https://blogs.edweek.org/edweek/campaign-k-12/2016/02/racial_bias_in_special_education_rule_proposed.html))

Of course evaluation is only part of the process. The emphasis here should also be placed on helping students of color with disabilities and their families in a way that is not inherently oppressive by perpetuating a cycle which often misinterprets learning styles of racial minorities. Ensuring that all personnel involved with the Individualized Education Plan (IEP) and Response to Intervention (RTI) process have been trained in and understand systemic racism and overrepresentation. In addition, students in overrepresented groups should be given opportunities at regular intervals to be reevaluated and potentially exit the system. Currently the frequency is once every one-to-three years, generally speaking.((Policies Governing Services for Children with Disabilities (Policy Manual). (2014, July 10). Retrieved August, 2016, from NC Dept of Public Instruction: Exceptional Children’s Division website: https://ec.ncpublicschools.gov/policies/nc-policies-governing-services-for-children-with-disabilities/policies-children-disabilities.pdf)) This policy likely needs revision. This would serve as a way to decrease overrepresentation brought on by failure to account for cultural differences, which would in turn direct scarce resources where they are truly needed and provide incentives for students who have the capacity to work toward the goal of exiting services.

Access to Rigorous Courses and Programs

1. Adopt universal screening processes for academically gifted programs so referral systems are as objective and inclusive as feasible, and to reduce unnecessary variance in practice by district. A standardized process that sets parameters but allows flexibility for the unique nature of communities is paramount. Broward County Schools (FL) reduced racial gaps in identification of gifted programs by utilizing a universal screening process that assessed all second-graders.((Dynarski, S. (2016, April 8). Why Talented Black and Hispanic Students Can Go Undiscovered. New York Times. Retrieved April, 2016, from https://mobile.nytimes.com/2016/04/10/upshot/why-talented-black-and-hispanic-students-can-go-undiscovered.html?referer=https://t.co/QL730F1v5S&_r=1)) This replaced a system of parental or teacher referral. Paradise Valley (AZ) Unified School District has created a gifted identification system that responds to the needs of the community.((Brulles, D. (2016, March). High-potential students thrive when school districts develop sustainable gifted services. Retrieved October 12, 2016, from https://edexcellence.net/articles/high-potential-students-thrive-when-school-districts-develop-sustainable-gifted-services)) The district uses a multifaceted identification process and embeds a gifted specialist in each of the district’s elementary schools to train teachers and staff to recognize high potential. With a large Hispanic population that often gets overlooked, the schools identify students using measures and assessments free of cultural or linguistic bias. As a result, the non-white gifted population has doubled in 2007. We recommend that North Carolina districts evaluate similar approaches to AIG identification processes in order to improve racial equity and improve access to AIG offerings. Making the assessments multidimensional (not relying exclusively on test scores), focusing on potential and not just performance, and looking at subjects beyond just reading and math could all prove beneficial. Districts should adopt similar process for access to advanced coursework.

2. Train teachers and counselors on the “belief gap.” Emerging research has revealed the significance of the belief gap (also referred to as the Pygmalion Effect): frequently, the absence of students of color in rigorous courses is not the result of an objective lack of readiness, but is instead due to teachers and counselors subjectively determining that students are not well-suited for the courses.((Finding America’s Missing AP and IB Students (Rep.). (2013, June). Retrieved October, 2015, from The Education Trust website: https://edtrust.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/Missing_Students.pdf)) This lack of belief in children of color denies them access to important stepping stones to academic excellence, with deleterious effects on their outcomes in K-12 education and beyond.((Stephens, L. (2015). The “Belief Gap” Prevents Teachers from Seeing the True Potential of Students of Color. Retrieved October 12, 2016, from https://www.forharriet.com/2015/05/the-belief-gap-prevents-teachers-from.html#axzz4IN20SigL)) Training on the belief gap can help teachers and counselors understand what to look for when assessing readiness for advanced coursework.

3. Audit course enrollments to spotlight racial disparities in honors, AP, and other rigorous courses. As an accountability measure, schools should undertake regular audits of course enrollments that analyze disparities in enrollment numbers among racial subgroups and that critically examine the criteria being used by teachers and counselors to determine student readiness for advanced coursework. If racialized gaps emerge that expose differential treatment, immediate interventions should be instituted to make the numbers more equitable and give all student equal opportunity of access.

Diversity in Teaching

1. Develop a fellowship program that incentivizes people of color to become teachers and offers them support to stay in the profession long-term. The number of young people entering the teaching pipeline is decreasing in North Carolina. Policymakers and practitioners are considering a number of strategies to widen the teacher pipeline, but too few of the policies focus specifically on attracting teachers to high-need schools who share the racial and cultural backgrounds of those schools’ students.

Thankfully, there are a host of examples throughout the country worthy of emulation. Programs like Profound Gentlemen (Charlotte, NC) is an incentive-based program designed to retain male educators of color through peer development, community building, and career opportunities.((Profound Gentlemen. (n.d.). Retrieved October 12, 2016, from https://profoundgentlemen.org/)) In a little over two years, the program has developed the largest network of black male teachers in the country. Other programs like Call Me MISTER (Clemson, SC) and African American Teacher Fellows (Charlottesville, VA) seek to offer financial incentives that attract teachers of colors.((Welcome to Call Me MiSTER®. (n.d.). Retrieved October 12, 2016, from https://www.clemson.edu/education/callmemister/ & African American Teaching Fellows. (n.d.). Retrieved October 12, 2016, from https://www.aateachingfellows.org/)) The New York City Public Schools has launched the NYCMenTeach program, which is similarly designed to attract Black and Hispanic male teachers to the profession.((Layton, L. (2015, December 11). Wanted in New York City: A Thousand Black, Latino and Asian Male Teachers. The Washington Post. Retrieved April, 2016, from https://www.highbeam.com/doc/1P2-39071771.html?refid=easy_hf)) We recommend that school boards and district- and state-level policymakers consider supporting similar models to boost recruitment of teachers of color in North Carolina.

2. Create teacher preparation pathways for communities of color that begin recruiting prospective teachers in high school, and that expand lateral entry opportunities for professionals from minority groups who show interest and promise as potential educators. Efforts to attract students of color early in their academic careers have shown promise as a model for bringing more of these students into the profession.((Bristol, T. J. (n.d.). Black Men of the Classroom: A Policy Brief for How Boston Public Schools Can Recruit and Retain Black Male Teachers (Issue brief). Retrieved September, 2016, from The Schott Foundation website: https://schottfoundation.org/sites/default/files/TravisBristol-PolicyBrief-BlackMaleTeachers.pdf)) As such, targeted efforts to recruit people of color by tailoring programs like the North Carolina Teacher Cadet program and the recently discontinued North Carolina Teaching Fellows Program to minority candidates could prove valuable in rapidly building up this important segment of the future teaching pool. Additionally, the state should make it as efficient as possible for those in other professions who would like to become teachers to do so, without sacrificing the quality of teacher preparation.

Culturally Responsive Pedagogy

1. Adopt a set of standards for culturally relevant teaching to assist teachers in understanding what competencies are needed to effectively instruct students of color. In the same way that there are language standards for English Language Learners with Sheltered Instruction Observation Protocol (SIOP), there should be research-based standards for cultural relevance and responsive pedagogy. The purposes of such standards would be to help teachers learn to instruct in ways that honor the customs, norms and traditions of all students; embed the diverse perspectives and histories of communities of color within the curriculum; and utilize these perspectives to inform best practices. Identifying competencies for teachers to aspire to will give practitioners a clearer picture of what equitable instruction should look like for students of color. This must be done with the understanding standards alone don’t change practice, but the level of responsiveness to students’ needs is what actually lead to competence. The focus should be on the application of cultural relevance by the instructor.

Teacher preparation programs should use the standards to reassess their curriculum and to develop new course offerings, since efforts to boost racial awareness will be particularly impactful during teacher pre-service training.((Will, M. (2016, May 10). Study: Teacher-Prep Programs Need to Deepen Educators’ Racial Awareness [Web log post]. Retrieved May 10, 2016, from https://blogs.edweek.org/teachers/teaching_now/2016/05/white%20teachers_diverse_classrooms.html)) Creating space for students to discuss race, choosing materials that reflect the communities of the children served, and factoring in worldviews other than those of traditional westernized societies are example of strategies that standards-aligned training can provide that will improve teachers’ ability to properly address cultural divides through pedagogy.((Kim, A. (2016, February 18). A culturally rich curriculum can improve minority student achievement [Web log post]. Retrieved February 18, 2016, from https://edexcellence.net/articles/a-culturally-rich-curriculum-can-improve-minority-student-achievement & Klein, R. (2015, December 4). What Happened When One High School Started An Open Conversation About Race. Retrieved January, 2016, from https://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/maplewood-high-school-race-relations-club_us_5660ad41e4b072e9d1c55755))

2. Implicit racial bias training for teachers and administrators to help break habits of prejudice and lead to more balanced treatment of students of color. Most of the racial disparities in discipline, special education, and AIG and advanced course enrollment are not the result of malicious intent as much as deep-seated, unconscious biases. But just because this type of racial bias is unintended does not mean it is harmless.((Staats, C. (n.d.). Understanding Implicit Bias. Retrieved October 12, 2016, from https://www.aft.org/ae/winter2015-2016/staats)) It is crucial for local school boards and district leaders to take affirmative steps to help educators deconstruct implicit racial bias and understand the nature of systemic racism. Research has shown that undergoing such training can lead to dramatic reductions in bias.((Devine, P. G., Forscher, P. S., Austin, A. J., & Cox, W. T. (2012). Long-term reduction in implicit race bias: A prejudice habit-breaking intervention. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 48(6), 1267-1278. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2012.06.003)) Guilford County Schools has been a leader in this area, with nearly more than 50 of their 127 schools participating in implicit racial bias training. We recommend that all other districts provide similar opportunities to their teachers and staff to help offset the impact of implicit bias on educational outcomes for minority students.

Glossary

Committee on Racial Equity

Due to the complex nature of many of the issues discussed by the Committee, it became important to qualify definitions for the purposes of establishing shared meaning. During one of the work sessions, the Committee developing a glossary to assist the reader when working through the document.

Race – socially-constructed classification of humans according to some physical features (e.g.; skin color, hair texture, body type, etc.).

Racism – (1) any individual or systemic belief, attitude, action or inaction, which grants or denies groups access and/or opportunity based on their race. (2) a pattern of social institutions — such as governmental organizations, schools, banks, and courts of law — giving inequitable treatment to a group of people based on their race.

Implicit Racial Bias – refers to the attitudes or stereotypes based on patterns and associations about a racial group that affect our understanding, actions, and decisions in an unconscious manner.

Disproportionality – disproportionate representation – over or under – of a given population. (e.g.; race, ethnicity, Socioeconomic Status, nationality, Limited English Proficiency, gender, etc.)

Racial Disparity – noticeably unjust or unfair outcomes based on race when individuals or groups are similarly situated

Disparate Impact – a facially neutral policy or practice has an unjustifiable effect of discriminating on the basis of race, color, national origin, gender, or disability.

[…] Committee on Racial Equity. With North Carolina’s increasingly diverse student population, intentionally and systemically promoting racial equity will be essential if the state hopes to dismantle historical racial and structural inequities to better serve its most vulnerable students. This Committee subdivided its work into seven domains: resegregation; discipline disparities; the opportunity gap; overrepresentation of students of color in special education; access to rigorous courses and programs; diversity in teaching; and culturally responsive pedagogy. The Committee’s recommendations include the following: […]